A new article for your reading consumption? What the WHAT? No, your eyes are not deceiving you. We’re getting back in the saddle which is quite exciting, but we’re going slower this time around. Curse you “adult reality” that requires us to work and make money to pay bills! This adulting thing is disgusting… just saying. If we could just focus on running our local gaming club and working on stuff for the Citadel, everything would be fantastic. With the start of this article, We’re going to target putting out something once a month. It’s not every week like it used to be, but hopefully it’s more sustainable with both of us working and all the gaming stuff we have going on.

We called this article, “The Great Railroad Debate”. We’ve heard it all, ‘Railroading your players is evil, all bad, it’s terrible, no good and you shouldn’t do it…’. Yet we still purchase published modules that are railroads and often play them in groups where we are not the GM without acknowledging it. So let’s talk about it a little and see if we can’t add some color, some context to the argument.

First, what the heck even is a railroad and why does it get so much flak? For those that haven’t been GMing for long or have somehow miraculously avoided this discussion entirely, a railroad is when a Dungeon Master, Storyteller, or Game Master either designs or uses an adventure or campaign in a way that forces a certain outcome by ignoring a player’s choices or agency. In other words, it doesn’t matter what the players choose, they are going to be narratively forced to follow the particulars of the adventure/campaign storyline as the DM/ST/GM directs. This in turn makes the players often feel like their choices don’t matter and then they don’t want to keep playing or they start doing random things since, after all, nothing they do matters anyways. There are both ‘good’ and ‘bad’ railroad methods, I’m going to talk about them and what you can do when you encounter them or find yourself doing them as a GM.

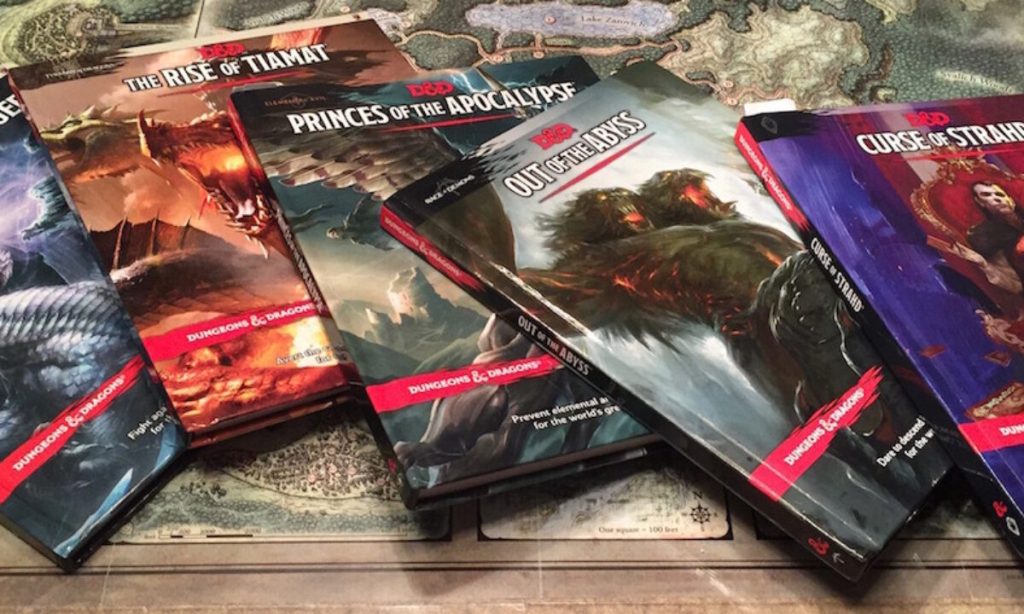

Railroads do occur naturally. One of the major places it shows up is with published adventure modules. Adventure Modules lead the characters from point ‘A’ to point ‘B’, then on to point ‘C’ with little deviation. The reason for this lies in the writing. It is incredibly difficult (and usually impractical) to write a module that effectively deals with any and all of the possible choices a player or group of them can make. Experienced GMs can weave the module around the players with improvisation skills that they have developed over time, but a new GM will typically have a harder time with not hyper-focusing on where the module should be taken.

Published adventures are pre-designed and written to take characters from one level to another and create ‘plot bottlenecks’. This can either be done with soft or hard railroading. Soft railroading tends to be an expected progression along a specific path with allowance and brief advice for what might happen with deviations and how to steer them back toward the main plotline. Hard railroading is when a problem is created that has only one solution. Hammer to nail, for example. Hard railroading limits player choice and player agency. Soft railroading likely does too, however it tends to feel like it less.

Do not mistake my words as negative or a bashing of published adventure modules. They serve a purpose in roleplaying games. They provide teaching tools to new GMs and help them know how to handle and construct encounters and travel, and they make it easier on an experienced GM with limited prep time to run a game. It’s hard to scoff or be negative at having everything ready to sit down and play.

Published modules are usually a great tool for new GMs to use to get their feet wet. They all have a beginning point and ending point. Some are better than others from a standpoint of agency and useful advice and clarity when running them, but they are all railroads. ‘Go here, do this thing, go here, do this other thing.’ It can feel like your choices don’t matter, but at the same time, that’s part of running and playing a module. You take the good – limited prep time for the GM, with the bad – limited choices available to make things work.

The next example of a natural railroad is your dungeon, particularly if you are using some sort of ‘mega-dungeon’. You start at the entrance and work your way deeper, hopefully successfully, then end up with loot and experience points. Sure, the way you approach the dungeons may change and you can choose which room you hit which gives you the illusion of choice, but at the end, you only have two choices, go deeper or go out. Dungeons don’t just mean the underground dungeons, it can be exploring a temple, a mansion or even a massive hedge maze. These are places that have a start point and an end point within a set area.

These types of railroads are good and often provide useful knowledge. In playing them then having a discussion after about things the group liked or didn’t like helps you develop a better rapport with your group and plan ways to increase everyone’s enjoyment at your table.

So, let’s shift to railroads and railroading that are more negative overall, the ones that cause the issues. These are hard, forced railroads, where the GM steadily rips away all choice until you have only one path to follow. Such behavior tends to make the players resentful and causes them to have a harder time getting into the story, stripping narrative immersion. After all, their character, in these cases, has become a side piece to the main story the DM is telling.

As an example, consider the following (adapted from an actual experience I had as a player within the last year):

GM – “A forty foot chasm lies before you with a frayed bridge crossing it, swaying in the breeze”

Player 1 – “I use my dwarven knowledge and my fifty feet of rope to reinforce the bridge for the larger and heavier party members… I rolled an eighteen for my craft lore.”

GM – “You work for some time repairing the bridge and, when you are done, it appears much more sturdy and safe to cross.”

Player 2 – “We start crossing in single file, going slow and careful.”

GM – “When all of you are in the middle, the bridge gives way, plummeting you to the bottom of the chasm with a loud sploosh.”

Player 1 – “But I fixed the bridge with an eighteen… Fine, whatever.”

When this happens, it is typically because the GM didn’t listen and could not envision a way to allow the bridge to stand and still get them where they needed to be, and you develop a resentful group because of it. A lot of players complain about this type of GMing and stop wanting to play.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, you have the pure improv sandbox. Because of the preparation required, this can look like a sandbox, but it’s not. A sandbox campaign is so called because it’s like a box of sand. You can use tools and pile it up however you want, making any sort of sculpture you wish. As players, you can pursue whatever goals, rumors, or missions you choose, and ignore ones that you don’t. This does not mean that the world around you does not progress or change. In fact, part of the preparation for this is that the person running the game determines who the power players and groups are in the world and what their goals are and at least think about how they might go about achieving them. Then, as the players are doing what they wish, the rest of the world is also working to achieve their goals. The players can work to stop them, or help them, but in the end, they are not the only people in the world who are exercising their will.

This kind of game is extremely taxing on the DM/ST/GM. It not only requires a lot of up-front preparation, but it requires good improvisation skills. If you do not know what your players are going to pursue ahead of time, and do not have some kind of “heavy handed”, railroad-style plot type, you are constantly going to be reacting to what they do. That is not to say that these kinds of games are not fun. Both Josh and I run these kinds of games regularly, almost exclusively. But I do not want to suggest that it is easy. It is a lot of work and takes a good amount of practice. Both of us started with prepared modules when we first started running games.

Personally, I am not fond of removing player agency. At my tables, we’re all there to have fun and tell a good story. I am firm in the fact that everyone seated at the table should be having fun. If your player (or GM/ST/DM) agency is trampling someone else’s, it’s not fun. Consent in gaming is key and if a player isn’t keen on having it happen between your characters, then it doesn’t happen. It’s why we run sandbox games. But as long as you and your players know what you’re getting into, an occasional module or mega-dungeon here or there can be fun.

What do you think? Are you a fan of published adventures? Do you make your own in that style? Or do you typically run sandbox games? Or maybe something in between? Comment below and let us know or hop into our Discord and chat us up there. We love talking TTRPGs and hearing how other people run their tables. That’s it for this month, so until next, from our Citadel to yours, Happy Gaming!

- Joann Walles

Now on DriveThruRPG, from Angel’s Citadel… A brand new, original setting for the Cypher System! The Hope’s Horizon Starter Kit requires the Revised Cypher System Rulebook from Monte Cook Games.

Like what we do? Check us out at:

- Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/AngelsCitadel/

- Youtube: https://bit.ly/2FxBvJv

- Angel’s Citadel Discord: https://discord.gg/aeMrw8FfAv